Millions of tiny dots litter the canvas, each independently just a splotch of unmixed pigment but together a masterpiece of illusion that leads the eye to see complex, brilliant colors as the dots blur together. Though largely unappreciated when it was completed in 1886, Georges Seurat’s most famous painting, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, was one of the first to feature his new technique, now known as Pointillism, where deliberately applied dots together form a cohesive design.

Special statistical techniques may be doing something similar for the analysis of complex, multifaceted data, blending data points into smooth curves and providing insights often overlooked by traditional techniques.

An interdisciplinary group of researchers at Penn State has been pioneering the use of these functional data analysis techniques, adapting existing methods and creating new ones in order to meet the challenges of a multilayered research study on childhood obesity. By representing the growth of children as smooth curves, functional data analysis improves the ability to mine these data for patterns, even when a study contains a limited number of subjects. The ultimate goal: to identify a set of easy-to-measure biological indicators that may flag an increased risk of obesity in children.

The INSIGHT team–including (clockwise from bottom left) Matthew Reimherr, Francesca Chiaromonte, Sarah Craig, Ana Kenney, and others–meets weekly to discuss exciting results as well as new challenges that their data present. Credit: Nate Follmer

Flagging obesity risk

“If we can identify early indicators of obesity in young children, we can help parents and clinicians take preventative measures,” said Kateryna Makova, Pentz Professor of Biology at Penn State, who leads the biological side of the collaboration at University Park. “Our ultimate goal is to give clinical practitioners the tools to identify children most at risk of obesity so they can reduce that risk by implementing intervention strategies, such as educating parents about nutrition or recognizing an infant’s discontent (crying) as being related versus unrelated to hunger.”

THE ULTIMATE GOAL: TO IDENTIFY A SET OF EASY-TO-MEASURE BIOLOGICAL INDICATORS THAT MAY FLAG AN INCREASED RISK OF OBESITY IN CHILDREN.

The INSIGHT study–Intervention Nurses Start Infants Growing on Healthy Trajectories–originated with Ian Paul, a pediatrician at the Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, and Leann Birch, then a distinguished professor in the Penn State College of Health and Human Development, who set out to study behavioral intervention approaches for the prevention of childhood obesity. Paul and his team collected data from approximately 300 families during regular wellness visits to the hospital, tracking first-born children–and their parents–from birth until at least three years of age. In many cases, a second-born sibling was also tracked through the team’s subsequent and ongoing study SIBSIGHT. The data includeda variety of clinical information, as well as questionnaires about feeding and other behaviors, diet, and socioeconomic status of the family.

Paul reached out to Makova, who agreed to collaborate on the study so that they could also investigate a wide range of potential biological indicators for obesity risk. To do so, samples collected from INSIGHT and SIBSIGHT children and parents were used to generate multiple “omics” datasets on genomes and how they vary; epigenomes (chemical modifications of DNA that can influence how DNA is read); metabolomes (smallmolecules that are the product of cellular processes); and gut and oral microbiome (bacteria and other microorganisms living within the gut and the mouth).

“A lot of childhood obesity interventions are focused on school-aged children,” said Sarah Craig, assistant research professor of biology, who coordinates much of the study. “These interventions do help some children, but by this age many children are already overweight or obese, so intervention really becomes more about treatment. If we can identify kids who are most at risk of developing obesity much earlier, we may be able to prevent obesity from developing in the first place.”

Mountains of data

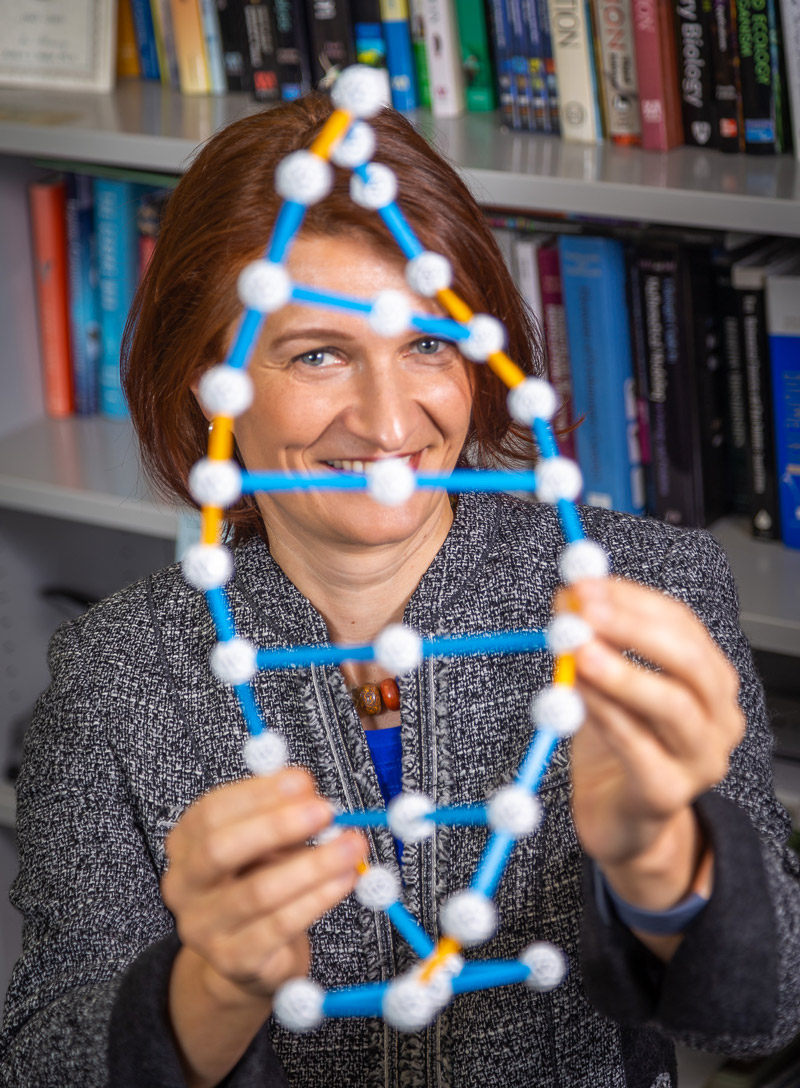

As the study expanded from clinical variables and a questionnaire to include ever-growing omics datasets, Makova turned to longtime collaborator Francesca Chiaromonte, Dorothy Foehr Huck and J. Lloyd Huck Chair in Statistics for the Life Sciences, who quickly brought into the team functional data analysis expert Matthew Reimherr, associate professor of statistics.

“This study measures a massive amount of information on a relatively small number of subjects,” said Chiaromonte. “In order to analyze these data properly, we had to combine a number of existing statistical methods very creatively and to develop some entirely new ones.”

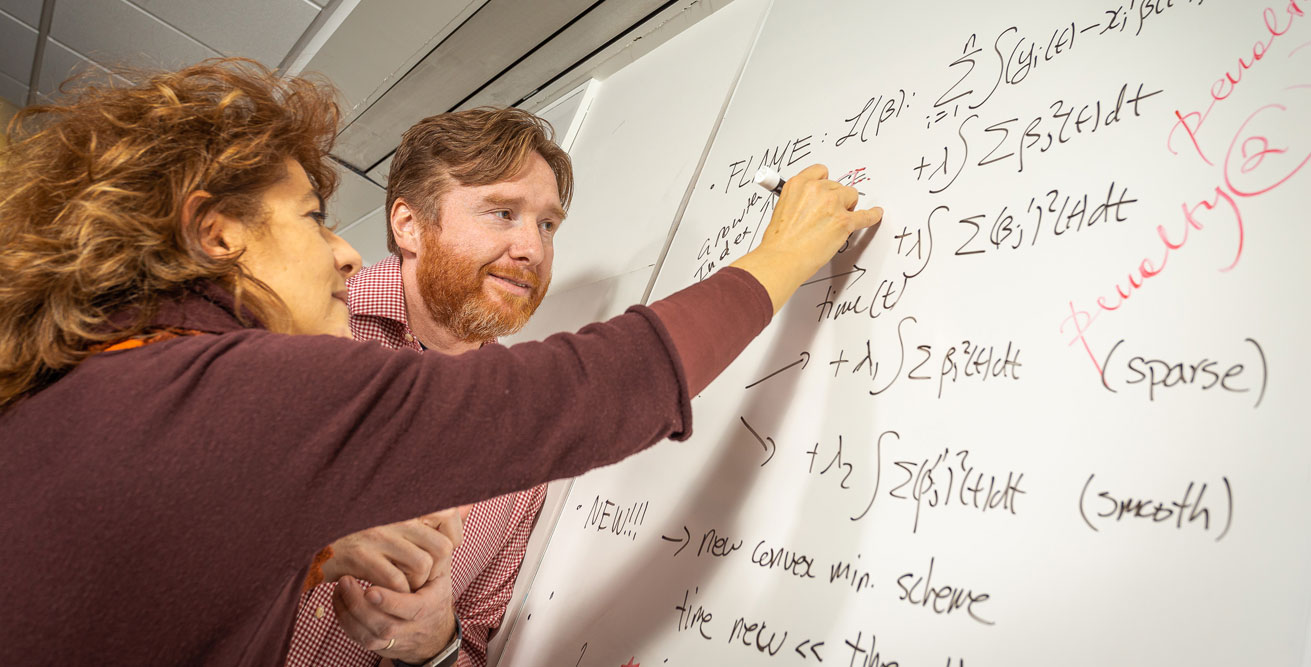

Each of the many aspects of this study–the various complex factors that can lead to obesity, the fact that children were tracked over time and that information was collected from more than one family member, and the large size of the omics data to be analyzed in conjunction with clinical, behavioral, and socioeconomic variables–brings its own statistical challenge. “The data are so rich that not every question is going to have an easy statistical tool that we can just immediately apply,” said Reimherr. “Each question adds more and more complexity, and we are developing better, innovative tools to handle it.”

The team is initially analyzing each of the omics datasets separately, starting with the identification of biological indicators based on microbiota and changes in the genome, and with ongoing work on epigenomic and metabolomic data. Their first paper was published in the journal Scientific Reports and highlighted important links between children’s weight gain trajectories and the composition of the microbiota in their mouths. Among other factors, the composition of an individual’s oral microbiota could be related to diet, and the team is collaborating with faculty in the College of Health and Human Development at Penn State to further explore the effects of diet.

Eventually, the team plans to bring all of the omics datasets together to study their joint effects on childhood obesity risk, which will bring a whole new level of statistical challenges.

“It’s not going to be easy, but we are determined,” said Makova. “What is the interplay among different features and predictors? Which ones are more important? Which ones are perhaps less important? All of this is going to be analyzed at the end of the study.”

THE FOCUS ON A CURVE’S SHAPE ALLOWS THE TEAM TO ANALYZE THINGS LIKE GROWTH SPURTS OR SLOWDOWNS IN A GROWTH CURVE.

Beyond a snapshot

Many participants in big biological studies come in for a day to have some measurements and samples taken and they are never seen again. Researchers analyze these snapshots, for example, considering a person’s body mass index (BMI) at the time they were measured–one dot on a graph of BMIs from many people. Then they try to correlate BMI with biological information, like the abundances of different bacteria in the mouth or mutations in their DNA.

But to get a clearer picture of the process of gaining weight in early childhood, the INSIGHT team took repeated measurements from children over their first three years of life, tracking them over time and producing what is called longitudinal data. Instead of focusing on splotches of paint on the canvas–a snapshot variable like BMI–the team’s approach attempts to find correlations with a more complete picture–a growth curve over time, and thus the propensity to gain weight.

“Mathematically this is, of course, much harder to handle” said Chiaromonte. “Functional data analysis techniques, which bring into focus the shapes of the children’s growth curves, allow us to make the most of having these longitudinal data for each child.”

This focus on a curve’s shape frees the analysis from many assumptions built into traditional techniques, allowing the team to analyze things like growth spurts or slowdowns in a growth curve.

“With functional data analysis, we have the flexibility to model complex dynamics,” said Reimherr. “If we find that a gene affects the way children gain weight, we can also establish whether the gene is actually more important in certain parts of their growth curves, which represent different ages. Maybe a particular gene that influences growth is only turned on right after birth. Or maybe growth spurts are driven by different genetic factors than other periods of growth. You can’t see this complexity with traditional regression techniques.”

Francesca Chiaromonte (left) and Matthew Reimherr discuss functional data analysis techniques critical to the interpretation of INSIGHT data. Credit: Nate Follmer

THE MORE VARIABLES YOU MEASURE, THE MORE LIKELY IT IS THAT THEY ARE RELATED TO EACH OTHER.

Smaller but deeper

An impressive aspect of the INSIGHT study is just how much information is recorded for each child and family, all of it very carefully collected at Penn State Hershey Medical Center to reduce error. This immense amount of data per person would not be feasible to collect from thousands or hundreds of thousands of individuals–a typical sample size for many omics studies, which rely on vast numbers to pinpoint often-subtle biological patterns.

Having deeply characterized information for a relatively small number of individuals does present a number of challenges. These datasets are sometimes called “ultrahigh-dimensional,” meaning that the number of variables measured on each subject is much larger than the number of subjects itself–e.g., hundreds of thousands of potential changes to a person’s DNA, or tens of thousands of bacteria types present in the mouth or the gut, compared to just hundreds of individuals. This makes it challenging to detect the effects that these variables may have on an outcome, such as the propensity to gain weight.

“The more variables you measure, the more likely it is that they are related to each other, so separating important signals from spurious ones becomes harder,” said Chiaromonte. “The data also get noisier and dirtier, and this can overwhelm the analysis if the sample size does not grow as fast as the number of variables we measure. We use careful preprocessing steps to try to clean up the data, and techniques that are designed to actually fish out elusive signals in ultrahigh-dimensional data.”

Getting the data to a usable form is a complicated process, but the team has developed preprocessing pipelines and data-reduction methods that mitigate these problems without losing the critical longitudinal nature of the INSIGHT data. These pipelines and methods, combined with the functional data analysis techniques, have allowed the team to capitalize on the depth of the data and uncover important results.

“We have found some really interesting signals in the data,” said Reimherr. “Our hope is that we can show people that these tools have some real power.”

The team believes that functional data analysis, especially if combined with data reduction methods, could change the way scientists approach omics studies. In fact, they recently published a paper in the journal Bioinformatics suggesting just that.

DEEPLY CHARACTERIZED, MULTIFACETED DATA GIVES YOU MORE INFORMATION TO PULL FROM THAT YOU JUST WOULDN’T HAVE IN LESS-DETAILED STUDIES, EVEN WITH MORE SUBJECTS.

“There’s a lot to be said about working with deeply characterized, multifaceted data,” said Ana Kenney, a graduate student in statistics who was involved in the INSIGHT study. “It gives you more information to pull from that you just wouldn’t have in less-detailed studies, even with more subjects, and functional data analysis is effective at exploiting these aspects that would be overlooked by more-traditional statistical techniques. It’s a different way of viewing the problem.”

And, according to Kenney, results from functional data analysis are interpretable by those without a strong statistics background, which is ideal for bringing their findings to practitioners and clinicians.

“This study is frontier, it’s not your run-of-the-mill stuff,” said Chiaromonte. “We need to fish through hundreds of thousands of predictors and try to relate them with the growth curves of a few hundred children. But having the longitudinal data and all the clinical, behavioral, and socioeconomic information recorded in INSIGHT goes a long way. Our hope is that, by combining deep information and powerful statistical tools, we can actually do something really important even if we don’t have hundreds of thousands of children in our study.”

The team has already found some notable relationships between weight gain in children and their oral microbiota–perhaps one easy-to-measure indicator of obesity. And with genomics results just about ready to be published, the dots are starting to connect, painting a clearer picture of childhood obesity, indicators of risk, and just how clinicians might intervene.